Powerlifting, Pressure, and the Alter Ego Effect

Many athletes adopt an alter ego in order to perform, the most recognized most likely being Kobe Bryant’s Black Mamba persona. By all accounts Kobe was reserved and very pleasant in everyday life, but in sanctioned basketball games, he became ferocious, cantankerous, and boisterous. This is where he needed to go in order to perform.

Recently, I ran a poll on my Instagram that sought out to see my followings thoughts on the mental and emotional aspect of lifting weights in a competitive domain.

Now, I think for the lay person, this is a concept that may be seen as over-complicating something that is rather simple. When you think about the sport objectively, it is rather simple, lift loaded barbells to a certain standard, a standard that is uniform across your specific federation, at all levels.

But, when we take an even further step back, aren’t all sports rather simple? Basketball is primarily getting a ball into a hoop, more times than the opponent. 100m dash is getting from point A to point B, as fast as possible.

You see, execution is one variable, executing under context is a completely different entity, in my opinion.

Basketball ceases to be simple when the stakes are winning or losing the championship game on the final play.

Running from point A to point B ceases to be simple when the race ahead can be decided by hundredths of a second.

There is a few concepts I will touch upon, throughout this article, the main one’s being: the mind’s effect on limiting our ability to execute, fear of failure, and dissociation and the development of an alter ego.

The inspiration of this whole write up, comes from my observation of athletics, being involved with them my entire life, and noticing the little idiosyncrasies from athlete to athlete, that allow them to perform in situations that are either high pressure, or high stakes.

Buckle your seatbelt, we are about to take a journey into the mind of the modern powerlifter.

The 6 Degrees of Mental and Emotional Separation

Within the poll, I focused on on 6 separate things that I believe are unique to each person, with each permutation revealing a bit about how an athlete ticks. Those being the following:

Are you more reflective or exuberant?

Does your mentality change discipline to discipline?

Do you need to dissociate?

What role does external variables play for you? I choose music specifically.

Do you find your mind is a limiting factor on execution from time to time?

Do you practice grounding and if so, how do you implement that?

I was fortunate enough to have around 495 unique votes on this poll, or around 83 per prompt. A small sample size of course, but I feel the answers were fairly indicative of my initial hypothesis.

I theorized that the modern powerlifter:

Is reflective and inward when it comes to “locking in”

Their mentality changes lift to lift, due to the demands of each lift

They need to at least partially dissociate from their normal disposition in order to execute

They rely upon external variables quite heavily, music being the main source.

The average person does not ground themselves and simply let’s nerves run their course

Here were the results.

89% of voters reported that they are internal and reflective when zoning in on a given attempt, or at least one with something on the line such as an all time PR, to win a competition, etc… To me, this is spot on with what I see at any given meet. When 3rd attempts roll around, at least in the waiting area, the animation and affect of each lifter dampens, not in a saddened manner, but rather a more serious manner. Even the most easy-going, free-flowing people tend to change a bit for these attempts. This can be further extrapolated towards training for most people. I am fortunate enough to work with a ton of people who are, for lack of a better term here, not exactly the most lasered in when it comes to disposition and even they tend to focus up a bit more on their heavy weeks. Furthermore, I think most people are not too animated because ultimately, the more attention you draw to yourself, the more theoretical pressure there is to perform. I see from some people, they need to back themselves into this proverbial wall in order to create a scenario mentally where they need to succeed or else the consequences will be dire. High risk, high reward in this regard.

A whopping 91% of people stated their mindset changes lift to lift and to me, I think my own commentary would be you probably already do this without acknowledging it. When you think about it, very rarely are people awesome at all three lifts, and typically have at least a partial disinterest in performing and/or training at least one, as a consequence. You see this mainly in people who are lower body dominant and as such, have a bit of disinterest in training the bench press. That said, I think the actual dilemma here is the execution associated with each lift. In terms of technical attention to detail, for most people the deadlift requires the least “precision”, as it is a simple movement in a vacuum. Squat is probably second, short of you being absolutely built to squat, in which you can flip flop the two previously mentioned. For most people, the bench press requires the most technical attentiveness. Set up, leg drive, unrack, scap depression, listen for command #1, descend, listen for command #2, cue bar path, listen for command #3. Doesn’t exactly lend itself to being out of your mind hyped and ballistic. Only people who are so calm, so collected, that you need to call the local morgue to see if they are really alive, I think actually bring the same mindset to each lift.

In a close call, 68% of people said they tend to dissociate for their most high pressure situations. More on this to come, but I think this is where most people can seek to gain, if they feel they are lacking in the 5th concept.

Only 56% of people said external variables play a large role in their performance. The closest of all of these, and looking at music in particular, it falls into the notion of, “You shouldn’t rely on things that are not promised in order to perform”. I certainly understand it, but I cannot relate personally.

67% of people stated that their mind can be a limiting factor when executing a heavier lift. Close again, but this one is certainly one I would be interested in diving in a bit deeper. I am very envious of the 33% who stated that it is never the case for them, and then furthermore, what they attribute that to. However, since the majority of this sample size does feel their mind is a limiting factor, this is why I think the dissociation piece will be interesting to observe as a whole.

Lastly, 69% of people practice grounding when experiencing pressure situations and a few people reported what exactly they use to do this and I found this very fascinating. Again though, I would be curious as to what the other 31% do when they get nervous, if they get nervous at all, and why they think this is. That is a totally different world to me and I cannot think of a single athletic endeavor that I have gone into where I was feeling nervous and just… let myself be nervous. That said, I suspected this as I know anecdotally speaking, people have reported this to me in droves.

Now that that’s laid out for us, let’s look into the three aspects of sport psychology I want to look at as a whole, and it’s context within powerlifting.

The Mind as a Limiting Factor

Rick Ankiel’s career as pitcher was destroyed as a result of mind-related limitations colloquially known as “the yips”. Ankiel, a lifelong pitcher, all of a sudden could not throw a strike consistently and would often times violently miss the strikezone 15-25 feet in each direction. He reported this feeling as hopeless and it forced him to change positions.

The mind has a funny way of limiting us. I once heard the adage, “It’s weird how you want something so bad, fight for so long, but once it is within reach, you hesitate”, and I admittedly resonated with this pretty hardcore. It can be as micro as a PR attempt or as macro as your next level up in the sport. Our mind tends to place restrictions where there isn’t any and for a lot of us, it takes a while to find the best headspace to rid or thwart these thoughts from permeating in. The mind can betray us in two directions, overthinking and underthinking.

Overthinking, or paralysis by analysis, is the one that most will suffer from. In order to execute a simple task, you need to be thinking simple thoughts. A lot of us carry a mind full of anxiety, full of things we held on to during the day, during the week, and as such, it becomes difficult to actually narrow in and focus on what really matters.

You will see this look like a lifter taking more time than usual to set up, more time than usual to get under the bar, saying things they don’t normally say, asking questions they don’t normally ask. Oddly enough, overthinking usually leads to a paralysis-type motion where the body becomes robotic and not fluid, movements are segmented and very rarely do they feel good as a result.

Underthinking, although less common, is when a lifter’s mind tends to drift and they can’t focus, for one reason or another. You see this manifest as a lifter being lackadaisical and lacking intent in their warmups, everything feels hard, they can’t seem to get things to feel right. This is common for people who choose to train through major life events. Very rarely do I see someone deal with a personal tragedy and report it being the best they have ever felt, the most locked in session they have ever completed.

For me personally, I tend to overthink quite heavily and I think it directly comes from environmental factors growing up in sports. I became so used to being criticized for technical issues that I became hyper-cognizant of what I was doing, how I was looking, at all times. When you are so worried about how a given lift looks, you fail to properly give the intent the lift requires. If you are about to attempt an all time PR, yes, you should have a cue running through your mind, but you should not be thinking about 10 cues and what the lift might look like if form breaks down. I also overthink the variables surrounding a lift. I preach all the time to only contextualize training on equal backgrounds, but fail to do that for myself sometimes. If you hit 500lbs x3 in the past, but sleep, diet, stress, and training was the best it ever was, it does not make sense to compare it to your 485lbs x2 which was hard, yes, but you have fell into a busy spell, bodyweight is down, and you are coming off an injury. We are sometimes victim of standards that are not actually there.

Fear of Failure

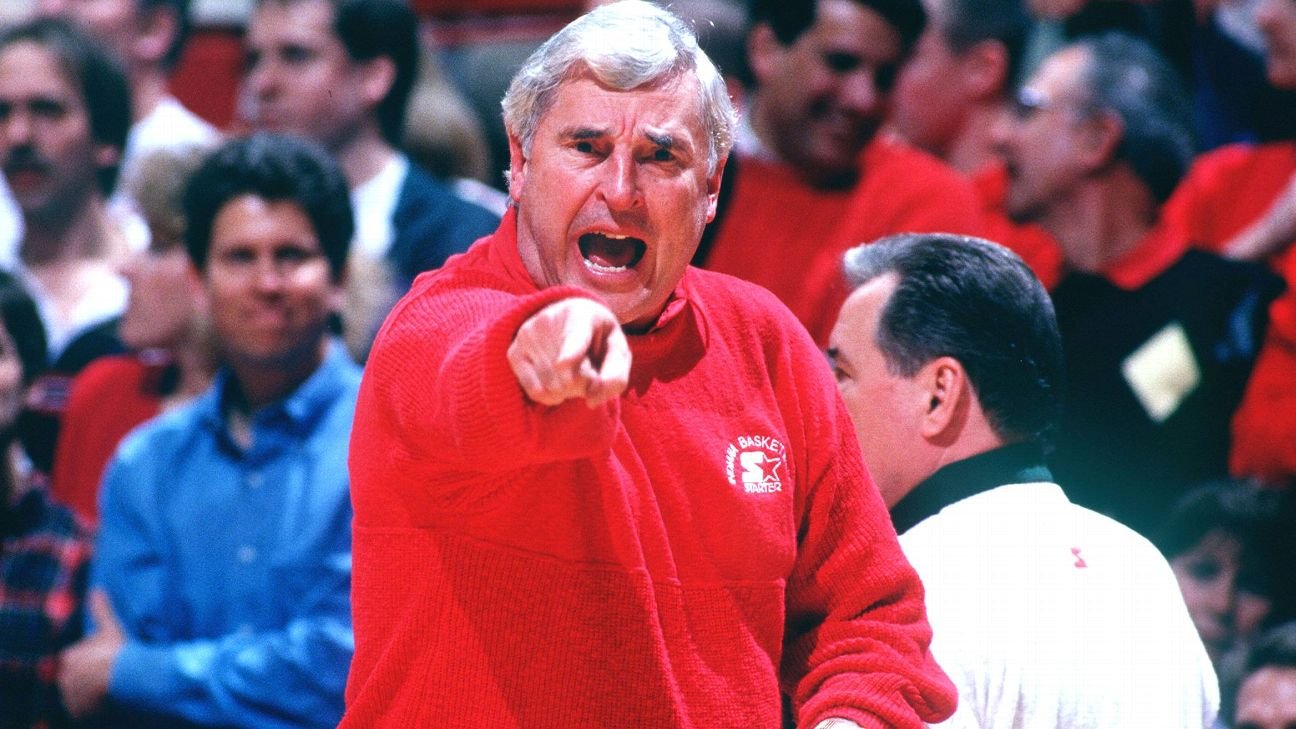

Bobby Knight, former head coach of men’s college basketball teams such as Indiana University and Texas Tech, adhered to a negative reinforcement model that created fear and perfection in his teams. Although Knight won 3 national titles in 29 seasons at IU, he created controversy for physically assaulting his players, belittling them, and being generally unpleasant.

The next most common mental phenomenon is the fear of failure, and to me, this goes hand in hand with mental limitation. Fear of failure is something that I have explored more and more recently, as I am curious as to where it originates in a given person, and it is something that I believe is a gift and a curse, depending upon the individual.

In sports, depending upon the sport, and of course, depending upon the system you were coached in, there is a very palpable sensation of what it feels like to mess up.

The school of thought is this:

Punish failure

When the athlete begins to associate failure with punishment, this will cut down on failure due to repercussions associated wanted to be avoided

When failure is limited, results improve.

Well, maybe in a utopian society, that would be the case, usually though, this is not what actually comes about from adopting this system.

For example, a coach implements system in which all missed layups make the whole team run. The intent here is to place the importance on making layups and creating a scenario where everyone is punished from your inability to execute, should you fail.

For the right individual, maybe this solidifies exactly what the intent was and they never miss another layup for the rest of their life.

However, I would argue for most, we begin to associate failure with: letting others down, opening the door for ridicule, and for many, total elimination from that situation entirely.

For many of us who grew up in the system, that could permeate later into life and not in a positive way.

If a lifter were to have an off day, miss a lift, and from my end, it is met with ridicule, admonishing, and general negative feedback, what is the likelihood they will feel comfortable to push themselves in a sport that is predicated on going just outside your comfort zone, consistently?

Not high.

What I have found, within athletics and competition, the best athletes tend to be the most fearless. The ones who are going out there, trying their hardest to succeed instead of trying not to fail. There’s a difference there.

An athlete that is trying to succeed, knows intuitively that failure is a formality and a possibility, but not one that has dire conseqeunces.

An athlete that is trying not to fail, is not allowing themself to exit their comfort zone due to what could happen.

As I mentioned, maybe some people need that type of sensation in order to perform, but they are few and far between and to be frank, that is not my philosophy and most athletes would be better of elsewhere if they need a dictator laying into them every fault.

The Development of the Alter Ego

Deontay Wilder, and many boxers for that matter, adapt an alter ego in order to tap in to a side of their brain that is less forgiving, less empathetic. For Wilder, who is a mild-mannered and polite person outside the ring, when he enters the ring to a fight, he has described it as similar to a caged animal being freed. Wilders then becomes the, “Bronze Bomber”, a fighter that boasts a record of 43-2-1 with 42 wins coming from knockout.

So, enter the alter ego effect.

I think for most of us, who fall victim of mental deficits when it comes to unlocking our potential, adopting a persona that temporarily allows us to dissociate from that negative thought process is something that can and should be developed in order to do the things we ultimately know we can do but struggle to actually do.

Now, I am aware some of this is a little “cringe”, meaning, you don’t have to pretend to be someone you are not, that is not quite what we are going after here.

Dissociation as a tactic is allowing the pessimistic side of your brain to be pushed aside in favor of the confident side, even if it is just for a brief moment.

Although some athletes quite literally change their persona completely, others use tactics to ground themselves in order to make the goal as streamlined as possible.

The best example I can think of this method, would be 5x CrossFit Games champion, Mat Fraser, who was known to work himself up into quite the frenzy before entering the competition floor.

He would dry heave and sometimes actually vomit, reminding himself that (whether it was true or not) other competitors were just as good, if not better, than him. Instead of letting that be a deterrent, it further allowed him to focus on the things solely in his control, which I feel is 100% applicable to powerlifting.

Yes, sometimes you enter a position where how others do, does effect you, however, what they do, is not in your control short of you actively sabotaging them to do poorly. So why bother with that mental aspect?

Mat Fraser, who was 2nd in 2014, 2015, and placed 1st in 2016, 2017, 2018, 2019, and 2020 in the CrossFit Games, was borderline maniacal when it came to making sure all variables in his control, were accounted for.

For others though, it is not that simple.

As humans, we carry insecurities and for a lot of us, are not confident at all times. Again, we are getting into actual psychological concepts that are above me, but this can certainly be attributed to a host of factors such as environment, natural predisposition, and things that happened in our past that don’t quite allow us to be comfortable in our own skin, all the time.

For those who tend to fall in this camp, the alter ego and the ability to tap into that for when it is needed, is something I recommend exploring.

No, I am not saying you need to suddenly start screaming and yelling and talking trash to unassuming people in the gym, rather, learn to access the side of the brain that allows you to feel the most comfortable.

Here is my experience, maybe you resonate!

In the gym, I am very self-conscious about my ability to execute. I would be lying if I said when attempting PRs, the thought of, “I don’t have this, I will fail”, didn’t cross my mind, virtually every time. It would be the worst thing for me to fail a lift in front of a busy gym that certainly has most of the members looking over and watching me, like, actually could not think of anything worse.

However, over the years, I have developed routines/techniques that allow me to rid my mind of these thoughts, again, temporarily, in order to do what I am supposed to do.

For me, it starts with music. I have my songs, the ones that I always go back to, that allow me to experience the feeling that I am a god, not literally, but figuratively. This is necessary for me, but you might not need to go this severe into dissociation. I am very aware that I am not the strongest person on earth, or even in my weight class, however for that moment, you cannot tell me otherwise.

Then it comes with my routine. If I can nail my routine, I know that is one less variable that will effect the performance and execution of the lift. This is why I practice said routine from the bar, all the way to top end set.

Then lastly, it comes with expression. Many who have trained with me, can attest I am saying things to positively motivate me and reassure me as well.

Things like:

You’re safe, these guys got you. (Referring to people spotting me)

You have this Erik. (Simple, but I am acting as if this is the alter ego speaking to me)

Reciting cues. (Trust your tempo, be aggressive)

This is what you do. (Reminding myself that I am someone who historically executes in high pressure situations)

Then finally, the breathing that resembles an emotional breakdown. This is something that I can acknowledge consciously, however I perform subconsciously. I tend to hyperventilate and then control these breaths into a few longer ones and tend to let out frustration grunts. This all sounds funny to write out, but it does help me and this may be pent up frustration that just manifests during this time.

All of this, allows me to become Erik the powerlifter, while Erik the person is pushed away.

Erik, the powerlifter, is confident, is aggressive, believes in himself, does not see failure as an option and is not afraid to fail.

Erik, the person, is insecure, feels unprepared, and will actively talk himself into not doing the things he can objectively do, based upon historical data.

I recognized this in myself early on and is something I have adopted since my team sport days. I learned that, for me, when I think too much, I do not perform. When I am free in my thoughts, and honestly, happy, I tend to perform better.

There is an alter ego in all of us and we all have the ability to tap into it. This is not a method that should be used every single day in the gym, as not only is it emotionally taxing, it can be detrimental to your training as a whole, we don’t need to access our demons (really ever) for a tertiary set of bench presses @ 6 RPE. I actually think there is merit to using this tactic sparingly as you can actively learn how and when to use it, and how to bring it on, instead of letting it blend with your outside the gym personality.

Pressure

Sydney McLaughin-Levrone, an ace 400m hurdler and recent open 400m runner, has overperformed at virtually all events she has participated in over the last 3 years. Although a sentiment some athletes share, she believes pressure is an illusion and only what we make of it.

To end this write-up, I want to state what pressure is and what pressure is not.

I see a lot of times, athletes are under the assumption that their results dictate how people view them in their everyday life. I have some things to say here that may be tough to here, but might also be freeing in a way.

The truth of the matter, is people don’t really care about our training, and if they do, they care about it from an aspect of how you are doing/feeling, not what you are lifting.

Read that again.

Too many times, people fall victim to social media traps of needing to perform for their audience, and recently I was guilty of this myself.

You should be training because you love training, not because you feel the need to impress your social media following with your PRs.

How is one to feel if and when they go through a slump and then their self-worth plummets when people aren’t as impressed?

The fact of the matter, is people are not paying as much attention as you think they are and very rarely do they know the context of you, and your training.

And hell, let’s say they do care, and are malicious and meticulous about praying on your downfall, what does that say about them? I do not know about you, but I have a lot more things to worry about during the day that fall under the category of importance that don’t fall under monitoring someones social media to see when they will finally break.

How lame is that, when you think about it?

I am fortunate to work with a variety of athletes, who have different mindsets and see things differently.

I really am protective of my people in this regard as some feel as if others are progressing faster than them, that they will let people down should they fail, that they are not fit for the sport as they aren’t of a high absolute strength level.

Unfortunately I do not know what lifting was like pre-social media, but I would have to make an educated guess that is was not as mentally strenuous as it is for young people getting into the game now, and others who are seeing the ugly side of it.

When it comes to pressure, it truly is an illusion.

You should want to do well.

You should expect to do well, granted context supports it.

You should not feel as if this is life or death.

The people at the highest level of the sport, are probably disappointed when a close meet does not go their way, but I cannot think of a single high level lifter who in turn, thinks they suck and/or think their self-worth is attached to their performance.

Regardless if you make that deadlift to win the meet, the sun will shine the next day. The people close to you will love you the same. Your coach will look at you in the same light as they always did. You will have another opportunity.

Pressure makes diamonds, or so they say, and it is a beautiful thing having something tangible and meaningful on the line.

However, it is not everything we make it to be.

What solidified this for me, was there was 2 times in my career I would say I “under-performed” relative to expectations.

2021 Junior Nationals, my first meet going 7/9 and not PRing my total.

2023 Massachusetts Spring Classic where I again, went 7/9 and did not PR my total albeit I was under significant injury and stress.

My people looked and treated me the exact same after both of these meets, as did they after my fortunate win at Regionals and any other meet I have done.

The people who matter to you, will always be there for you. You are not held up to a standard of performance besides your own.

So, for what it’s worth, when you go to your next meet, realize that if you have a solid coach who has your best interest in heart, you prepared and in good faith, did everything you could to provide the best possible outcome, everything else is outside your control and there is no pressure to perform beyond the expectations you and your coach laid out before hand.

If someone who is at an Olympic level and has set many world records can enter a high level race without pressure weighing them down, I think we all can enter our given meets with the same.

Conclusion

I truly hope you all took at least something away from this, if you don’t agree with parts, that’s okay too, I think there is a certain individual that does not respond well to this approach. As someone who has for most of their life, felt like an imposter, these tools have helped me and if I can help just one person feel more confident on the powerlifting platform, then this post did it’s job.

Well wishes to you all.

To Utopia,

Erik