Peaking in Modern Powerlifting: To Taper or Not To Taper

Not another article on peaking and tapering! Reasonable reaction, but as always, hear me out.

In modern powerlifting, I feel as a collective, we have done a great job of unlocking athlete’s “potential” with proper and more sound peaking protocols, however, there is a still a mystery on what those protocols entail and how to implement them, whether it be for yourself, or for athletes you work with.

I will be transparent here, everyone will have a slightly different method as to what I will lay out in this article, that doesn’t make me anymore right, or them anymore wrong, the proof is within what the athlete responds best to at the end of the day.

In order to give this topic the best chance of resonance, we need to establish some ground rules that we will refer back to, things like:

What Do We Seek To Accomplish When Peaking?

Why Do We Taper?

The Overreach and Taper Peaking Protocol

The Momentum Peaking Protocol

Then we will break down some specific examples of peaks/tapers from my own roster, and breakdown why we used the approach we did, what results it yielded, and what we needed to do beforehand to make sure the athlete was on board with each protocol.

What Do We Seek To Accomplish When Peaking?

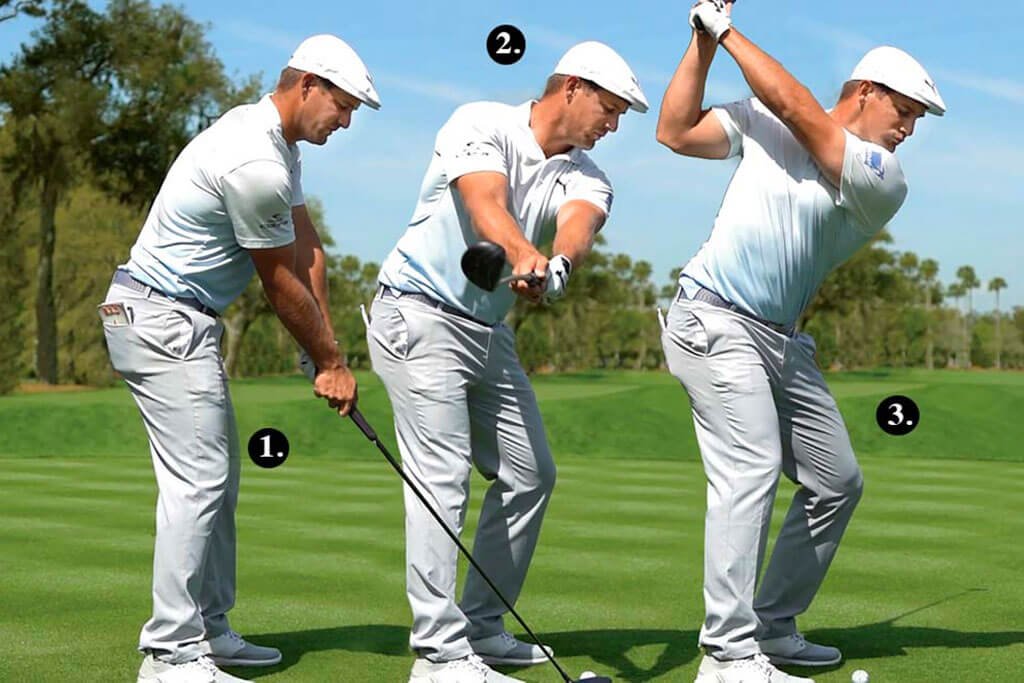

A golf swing, shown here by Bryson Dechambeau, needs constant technical reinforcement in order for the athlete to feel confident in it, you can grease the groove more often with this type of movement as in relative terms, it is not as destructive to the body as things such as: form tackling in football, repeat 100% effort sprints, etc…

The age old question, what are we actually doing, when peaking? Well the classic sport answer is achieving, and being able to express, the most specific task of your sport as possible while seeking to maintain fitness and dissipate fatigue.

Lot of jumble there, let’s make it even more simple.

Peaking is when you should be ready to do exactly what your sport requires you to do in competition and at your highest possible level.

Sounds pretty simple right? Well, it can be. It also can be the most challenging part of the sport.

In the sport of powerlifting, we seek to be the strongest on single repetitions on the squat, bench press, and deadlift.

We also seek to be the strongest on all of those on the same day.

What resonated most with me, was the concept of strength vs. skill.

Strength, as a general characteristic, is extremely stable, meaning it takes quite a bit of time for your muscles to produce less force outright.

Skill, however, is extremely unstable. I touched upon this in my article about feeling good vs. feeling strong, but in essence, we need regular motor pattern refinement in order to feel “in-the-groove” with our sports movements.

If this does not resonate, let’s take a very precise sport like golf, and then a maybe less precise and more ballistic sport like American football.

Intuitively speaking, if you have a golf match in 2 weeks, would the bulk of your final preparation for this be straight up rest? Of course not. You would show up to the match and your swing would feel all kinds of off due to lack of reinforcement with that pattern, a highly technical pattern.

Let’s take the same scenario for football, it probably makes a little more sense for the bulk of that final 2 weeks of preparation to be rest and general walk throughs. Why? Well depending upon the position you play, there is only so much effort you can put in, in a given week, knowing how much pure output is necessary on game day. The movements require skill, do not get me wrong, but stepping towards the left and shooting your arms out as a linemen does not need daily refinement like maybe a golf swing, or to a lesser extent, a tennis serve, maybe does.

So, as you can see, there is a blend of making sure we have enough skill practice to make sure the movement pattern feels second-nature, but not overdoing that to the point of fatiguing the associated muscles, inhibiting their ability to produce force.

It was once common notion to rest and take several days off before a powerlifting meet, I would be hard-pressed to say this approach is favored by any modern coach, as with what we know now, being strong is not directly correlated to feeling fresh.

Why Do We Taper?

Again, in the classic sense, tapering is dissipating fatigue via reduced workload, intensity, or both, in order to elicit top end performance.

I think over the years, most coaches are stepping away from traditional tapering strategies for a few reasons.

Tapers are highly individual and what works well for one person, will kill the momentum of another.

Tapers are not as consistent meet prep to meet prep. Basically, what got you to PR by 10kg when you were squatting 100kg, might not be what gets you to 200kg.

Tapers might not be necessary. It has become simply a rite of passage, to perform a taper into a powerlifting meet because, well, that’s what you do. Technically speaking, tapering is the removal of fatigue while keeping fitness as high as possible, a usual sign of fatigue is performance deterioration, if there is none, why would we taper and do less? Especially when we know that skill is a big component towards strength expression.

Now, this doesn’t mean tapering is useless. We have all had a scenario exist where truly, we were fatigued by our training volumes and performance was stagnant/regressing, only to dissipate said fatigue and exceed our intuitive capabilities a week, sometimes a few weeks, later.

Tapering is not magic and we should not view it as such. The longer and longer you compete in strength sport, the less and less you can bank on a taper to produce massive results.

The Overreach and Taper Peaking Protocol

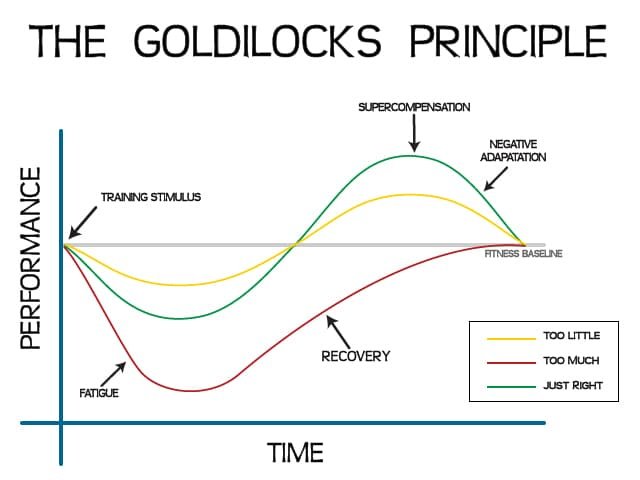

Tried and true method of preparing for powerlifting meets, apply stress, elicit adaptation, remove stress, super-compensate. As you can see however, several things have to go right in order for that removal of fatigue to elicit a supercompensation effect and not simply return you back to baseline.

Generally speaking, most literature or anecdotal references you find, will highlight something like this to prepare.

This is usually accompanied by the “peaking block”.

Full-disclosure, this is a valid and tested protocol that has made many of my own lifters display their strength in ways that maybe neither of us were anticipating in the past, and for the right person in the right situation, it makes sense.

The basics of this approach, are as follows:

For several weeks, we train at, and then for a brief time, slightly exceed, maximum recoverable volume/intensity, only to dissipate that workload at a given time domain leading into the meet.

Generally, this is the heaviest portion of our training time, meaning we cannot spend much time here as chronically, the effect of consistent exposure to top end weights can lead to greater risk of injury as well as negating other aspects that need to be addressed.

You will feel good, until you feel bad, until you feel good.

Generally, most people who you see hit numbers they grinded out or even failed, with ease on the platform, used some form of this method, highlighting the importance of fatigue dissipation and how fatigue can mask top end strength.

Early on in my career as a coach, I leaned on this pretty heavy as I came from a classic strength and conditioning background in which this is a fairly typical. How I went about it then, was way different than I would go about it now, however.

Let’s say, pre 2020, most of my approaches would look like:

6-7 week “peaking” block.

Last heavy deadlift is taken 10-12 days out, last heavy squat and bench around 6-8 days out.

The week of the meet, work up to openers on each lift.

Maybe your final session, you work up to last warmups.

All accessory work is removed.

Again, these days, I think this might be one of the worst ways to go about it, personally speaking. I will touch on how I approach this now, but there’s a reason this style of approach is still fairly popular, let’s dig into maybe why that is.

Ease of implementation.

Simply put, this method is a bit easier to explain, a bit easier for the athlete to buy-in, and is in line of what we maybe intuitively think we should do, when preparing for a meet.

A bit more intuitive for selecting attempts as your heaviest attempts are closer in proximity to the meet.

With this approach, your heavier lifts are going to be closer to the meet itself, so having confidence in a lift, or lack there-of, is going to, in theory, be a benefit to deciding on attempts.

For beginner/intermediate lifters, there is no reason to over-do this side of the equation as they are probably getting stronger in spite of protocol, not because of it.

It is not uncommon for beginner/early-stage intermediates to pretty much linearly get stronger into the meet, organically. Trying to make a complex block structure scheme, is simply not necessary.

More in line with what 90% of lifters/coaches are doing around you.

When you see people entering their “peak block”, hitting “taper weeks”, etc… psychologically speaking it puts you at ease with what you are doing, is matching what others are doing. You might think I am splitting hairs, but I have dealt with quite a few “why is X person doing Y and I am doing Z”, the week of a meet.

Now, you might have noticed I keep putting “peaking block”, in parentheses, this is for a specific reason. There is a notion that when you get close to a meet, you need to train a certain way and the “peak” is the condition we are trying to achieve.

Where this comes from, is early periodization modeling looked a lot like:

Hypertrophy training (Trying to get the muscles bigger)

Strength training (Trying to get the new, bigger muscles, to recruit fully which manifests as more force)

Peaking (Trying to prepare for the most specific bout, aka, your competition singles)

It is not uncommon in models like this, to be in the 8-10 rep range for months, the 4-6 rep range shortly there after, only to change to 1s to 3s when you get close to a meet or test.

Sounds good in theory, but seldom does this manifest into new gains when you circle all the way back to your test phase.

Models such as DUP (daily undulating periodization) and block periodization concurrently, have phased this way of training out, and probably for good reason, as for the natural lifter, it is not necessary to take multiple months off of exposures above 85% or dare I say, take multiple months off of singles, depending upon the person. Instead, you are touching characteristics of each of those concepts, per week, and over the span of many blocks, you shift the focus towards what the goal of the block is, based upon the needs of the lifter.

As mentioned, nowadays, I certainly still use this principle for my own lifters, however, it is not nearly as stringent as say, before 2020. I will highlight a few examples of my own lifters below.

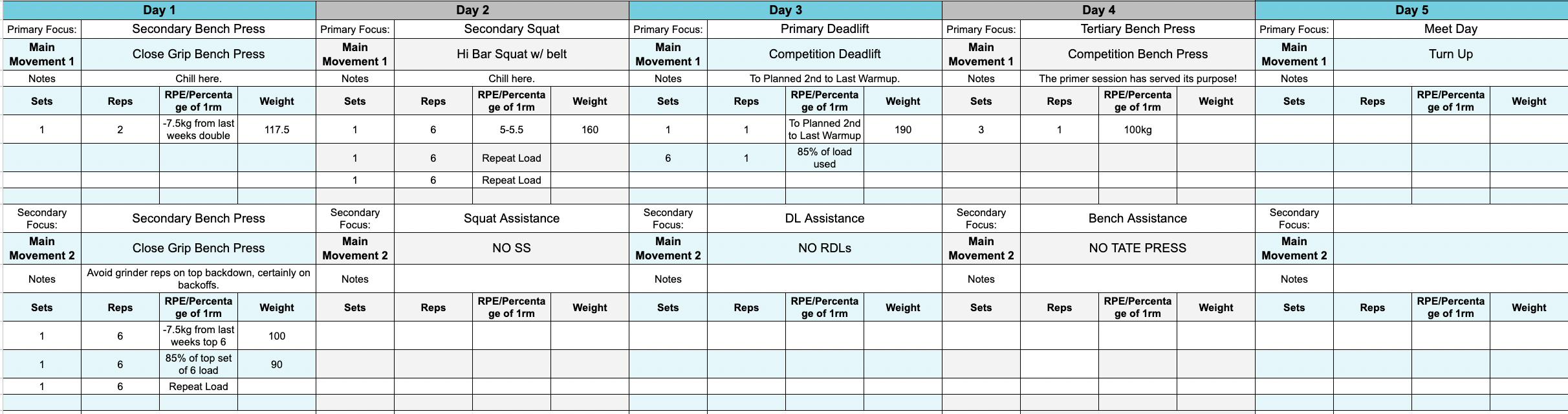

One of my athletes here, Mike Iascone, with his one week out training. As you can see, volume is still quite high, relative to proximity to the meet, and for him, intensity pretty high as well, he was able to hit an all time PR single on squat, bench, and deadlift this week. We even exceeded our load caps a bit for bench press as he was moving incredible and adapting to training volume 1-1 each week. Now, training leading into this week was much more tame, especially early on.

Here is Mike’s training a week out. For him, I noticed big disrupter assistance movements like split squats, RDLs, etc… were low hanging fruits to remove. This is not the case for everyone. You will also see intensity dialed WAY back on squat and deadlift, however, bench press only a minor drop. If you are treating all 3 lifts the same, more than likely this is because you are under the guise that more rest = stronger for all 3 lifts, when, in reality, its more complex than that. Mike went on to match his best squat in prep, taper into 5kg more than his best bench (with 5kg more to spare) and a whopping 15kg more than his best deadlift.

Dani LaMarca, featured a bit more intensity per session, coupled with lots of accessory work the final week leading into her most recent meet. We had to play safety on deadlift, as we unfortunately rolled on an SBD scheme that we thought would take, but did not have a positive effect. Much like Mike, week 1 training did not look this intense.

Dani’s week of the meet training is different from Mike’s in that, we kept a lot of the assistance stuff in, average intensity was much higher as well. 2 things are important to note, I don’t take “openers” for the sake of practice, it generally falls as a last heavy exposure around the 85-90% range, for the bench press at least, and the only reason we went up to that range on deadlift, was we missed out on heavier exposures so I banked on training the lift heavier, closer to the meet because a taper was only going to maladapt her. Dani went on to squat 363lbs for an all time PR, bench 192lbs for an all time PR, and deadlift 341lbs, up 16lbs from her final heavy pull, just 10 days prior.

The Momentum Peaking Protocol

More and more these days, I am defaulting to this type of scheme for people’s meet prep training and I feel I have a robust sample size, from my own roster, but also from others, that at the very least, this approach is a bit more consistent and relies less on betting that a taper will hit. But what does this protocol entail? Stay with me now because at first it might sound complex, but it couldn’t be more simple, in practice.

I call this method a momentum peak, however, really it can be looked as whatever run of the mill name you want, and I have seen it be called, “time to peak”, “block structure peak”, and a host of others.

Now, the actual cycle part of this, isn’t that special, however the distinction lies in all the blocks of data leading up to it. So if anything, this type of peak makes the previous blocks before it, infinitely more important.

In this type of model you seek to find a few things:

A block structure that has accurate data over at least 2 blocks.

To me, this is the single most important variable of deciding to use this as a peaking protocol. If you do not have data that a certain block length produces consistent results at the end of it, then you are playing with fire here.

A scheme that features regular top end loading on primary days with comp lifts.

If you tend to program very low intensity blocks, with very distant variations or distant rep ranges, again, your data will be skewed. This is not to say you need to be doing heavy singles the entire time, however, if you are spending time on your primary days doing SSB squatting, close grip benching (when you are a wider grip bencher), and performing sets of 8 on deadlift, you may find this data does not accurately reflect competition singles.

Bonus, but highly recommended if possible/feasible, aligning primaries closer in proximity to the days you compete.

Does this mean everyone needs an SBD day? No, not at all. However, with my own athletes, I personally feel we are able to reflect our training on the platform as accurately as possible, because we align primaries with the day of competition, so we have real-time feedback week to week, block to block, leading into a meet.

My athlete Michael Beaupre, who I will highlight later, competed on a Thursday at Raw Nationals, historically his Thursday would always be his lowest intensity session, so we shifted his training to have Thursday be the day we featured his primary squat, bench in order to align the blocks leading into the meet as accurately as we could.

Generally, I prefer, if we can, to have my athletes take their heaviest benches, after their heaviest squats, because again, specificity matters, if we know how much of a drop off there is from heavy squats that effects the bench, several weeks/blocks in advance, when we go to the meet, we won’t be blind-sided when it occurs with what in-theory should be the heaviest lifts of a given training cycle. Deadlift is the one that is the most variable, we will get into that in a bit as well.

So, too long, didn’t read, you need data on if a given week is consistently strong, you need somewhat heavy loading in a specific manner, and you should more than likely try to align the days of your primaries, close to, or exactly on, the day of competition.

Now, the tough part to this, is explaining to an athlete who is attached to a certain dogma of peaking, why they should consider this approach.

Again, we bank on a taper at the end stage of a peaking cycle and I do not care how much thought you put into it, there is a dice roll on whether that is going to take on each life.

However, the way I look at it, and what has resonated with my own athletes is the following:

Think of your best days in the gym, what was the 3-4 days leading up to it.

I am pretty certain most coaches, myself including, do not perform taper weeks, every single block, more than likely, there is no taper leading into these sessions aside from a slight reduction in volume/intensity a few days from a test/heavy day.

Consistently speaking, what sessions have felt strong, what sessions have consistently felt the strongest?

If this is a hard to answer, this is where your video and your block results matter!

So really, all we are doing, is looking to follow the same progression we did that yielded such incredible results, only instead of that final session being a heavy day in the gym, you are performing so in a meet.

I can sense the lightbulbs flickering now, but the first pushback to this would be, well what if I am too fatigued the week of the meet?

The counter to that would be, hopefully by now, we have established a trend on how many exposures you need in a given block to express strength, and that it is almost superfluous if the data is consistent.

Still not buying it? Let’s look at a few examples.

Michael Beaupre’s penultimate block before USAPL Raw Nationals. For many, many months, we found that almost regardless of how weeks 1-4 went in a given cycle, his W5 would always overperform. So, we decided to go up to around 8 RPE on each lift in that penultimate block for singles, assess how they moved, and then looked to run the same progression leading into the meet itself, starting at somewhat of a higher base. As you can see, Michael’s deadlift was the variable we had to play around with, as we noticed it performed better, and subsequently his health leading into his other primary session was better, having it be further out. Notice the primary squat and bench session, is aligned with the day of competition, Thursday, we had 3 blocks before this adapting to this scheme.

Our final week leading into the meet was modified only slightly, mainly to taper the deadlift more appropriately. However his secondary bench, secondary squat, and primer bench session, were identical. Michael was able to squat 474lbs at this meet, 308lbs with more in the tank, and deadlift 529lbs to secure a 1300lb total at 148lbs at the highest level of judging USAPL offers.

Brittany Boxer’s penultimate block leading into her most recent meet. With Brittany, for several blocks, we literally followed the same exact scheme going into the final week of each cycle, this being a 4 week block structure, and she would perform extremely well each time. She also mentioned with the other style of meet peaking, she would accumulate fatigue disproportionately to the work/strength she was obtaining, which is not uncommon. Much like my other female lighter weight lifters, her average intensity is fairly high the week of a test, almost across all sessions, and although maybe unconventional, the results were pretty substantial.

This is the week OF her meet. Yes, we want up to a PR set of 4, the week of the meet, on squat, because we had that trend. We went heavy on secondary bench, because we had that trend. Now, with her deadlifts being on Monday and Thursday, how did we taper that? We knew the 2nd deadlift session was always the stronger one, and we wanted to be strong on Saturday, not Thursday, so all we did was move the volume from the earlier in the week session, up to the normal “heavy” slot, and treat that as our “taper”. So you could make the argument, we only tapered a single session. She went on to squat 308lbs, bench 143lbs, and pull 336lbs, all with anywhere between 2.5 and 7.5kg to spare, as well as all time PRs on all 3 lifts, total, and DOTS. Grace Poirier, Jordyn Rocca, and Tayla Knapp also followed something similar and all had the best meets of their careers.

Clearly, I have become biased to this approach, but I think it would be a disservice to not talk about when you should NOT use this style of appoach.

You live a chaotic life that does not allow for continuity between sessions per week.

Pretty simple here, this approach requires extreme precision and if there is hiccups every single week, there is no way a trend can be established.

You do not do well, not knowing where you are at, in the moment.

What I mean by this, a week out, when you are still ramping up, most of your peers will be going very heavy, sometimes aggressively so.

If you are someone who NEEDS to know, within the final 2 weeks of prep, of where they are at, then this approach will not do you good mentally, as your heaviest lifts, technically, will all be a full block out. But I would just say not to view it like this, to be fair, however, it is valid for people who need that reinforcement.

You inherently don’t do well, knowing you are not doing a taper week.

Piggybacks off of the former point, some athletes develop a dependency on “the taper” and despite all education attempts, will not trust that process, if there is not taper associated, you might be thinking I am lying, but I am not.

Your meet falls outside of your block structure.

Now, the simple fix is to treat the furthest blocks out with an extra intro or deload week, however, somes times if you have to jump into a meet rather last minute, and it is 8 weeks out and your block structure dictates the 5th week of 5, or 6th week of 6 is the strongest, you might not want to get too cute with rearranging things.

All that being said, for my coaches in particular, this method takes a bit more work in the sense of:

Need to establish block structure many blocks out.

Need to have tangible results to go off of.

You need to actually watch your athletes heavy lifts keenly and with context that penultimate block in order to design attempts.

You need to have faith that their life is stable enough to not skew things out of your control.

However, when it takes, man does it take. More and more, I am trying to find blocks/schemes that are consistent and although I prefer this approach, only a small amount of my roster has used this to this point, I look forward to introducing it more and more as we go!

Conclusion

So if there is anything to take away, it is the common recommendation by most coaches, to do what makes you strong and do not deviate from it, just because you think you should.

If your 1rm goes up in a block you are doing 10s on your secondary, do so leading into the meet, assuming the trend is more than a block.

If you do not have massive fatigue accumulation, you do not need to taper, and honestly if you do, you might actually regress, which is of course, not the intent!

As an athlete, you need to be in tune with your thoughts/trends of your own training and do not let others cloud it. If you and your coach notice a trend, you can of course be skeptical, but if you are going to ignore that notion completely, my question would be why are you working with said coach/why are you being coached in general?

As a coach, realize if you want to use either scheme, there has to be context of several blocks leading into it and peaking and tapering is not magic. We have all seen people fail a lift a week out, and hit more the following week, and that is cool! But intuitively, wouldn’t we want out athletes flowing into the meet with momentum and total confidence and not have to bank on something that might not have the effect we intend? I think so. Food for thought.

To Utopia,

Erik