Ascending Sets vs. Top Sets vs. Straight Sets: When, Why, and How to Implement

I remember about a year and a half ago, I saw a coach make a decree that ascending loading and ascending volume was “lazy” program design and that it usually meant the first 2 sets of a 3 set scheme, were glorified warm-up sets.

After reflecting, I thought, and later came to the realization that not only was this statement vastly incorrect, it showed something that I personally believe is indicative of a greater issue. Any time someone speaks in absolutes, I tend to not really listen to them, in the sense of program design.

X is bad and Y is good, to me, is a very volatile statement as for every person who does not benefit from something, there is another 3-4 who swear by it.

But enough of the banter, you more than likely clicked on this article for 2 reasons:

You want to know why some people use different loading strategies.

You want to be able to apply this in some manner, towards your own athletes or yourself.

If it was neither of these and you just want to support me, hey, thank you.

Getting serious now, it was about 2020 when I opened up to the idea of loading schemes that were not top set + backdown or straight sets.

Not that 2017-2018 was a long time ago, but I really feel like it was all the rage back then to favor top sets and straight sets as it was fairly intuitive for it’s implementation.

In 2023, we have came a long way in terms of understanding why certain things work in spite of how unconventional it seems on paper. See: high rep sumo deadlifts, ascending volume, time to peak models, no taper training, non-specific training leading into meets, etc…

Now, I will say this is a topic that some coaches will have alternative takes to in terms of their own personal application, which is fine, and I want to make it clear, this is how I think, not the end all be all and if you disagree and are seeing improvement in a different application, I am not the one to say stop doing it that way!

I will break this down into what the strategy is, the pros and cons of said strategy, how I tend to apply it, and then tag a personal example.

Ascending Sets

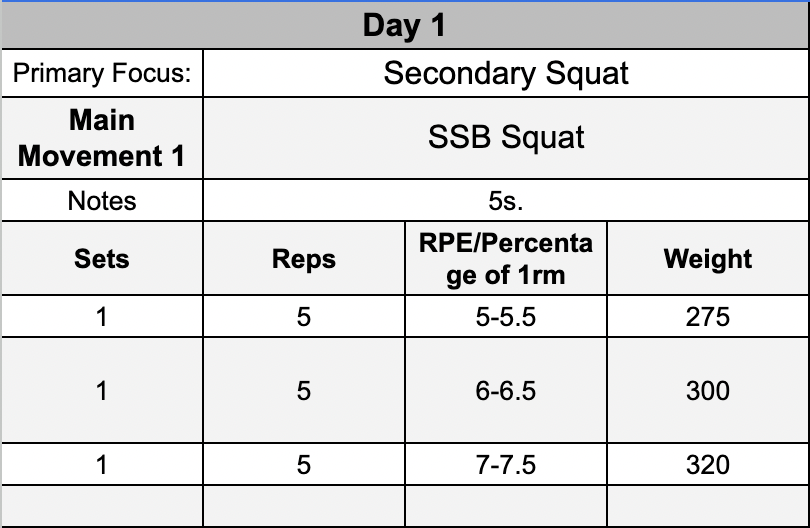

My own personal training block here, I have never ran SSB as a main movement, so for me to take guesses of where I should be for 5 reps per set based off percentage is going to be drastically off in either direction. Ascending loading allowed me to feel out the first 2 weeks of where my limit was while learning the bars natural sway. After 3 weeks of ascending volume, I switched to a top set, backdown scheme.

Ascending sets are an offshoot of what I believe was initially called pyramid sets, in which you would add weight each set, however decrease reps.

Ex. 1x5 @ 200lbs, 1x3 @ 220lbs, 1x1 @ 240lbs.

The main difference with ascending volume, is you are performing the same amount of reps per set, while increasing weight on the bar.

Ex. 1x5 @ 200lbs, 1x5 @ 220lbs, 1x5 @ 240lbs.

The main critiques I see of this method is the fact that it is overly fatiguing and limits the loads that you can use on the final set, in which, my reply would be 90% of the time I see this used, that is the intention.

The other pervasive critique would be the first couple sets are not effective enough to drive adaptation. I would disagree again. Sure, you can make the active choice to sandbag them, that is one issue, however, if you are educating the athlete on how to pace these correctly, by the end of most training cycles you will be surprised would %s of 1rm athletes are handling on the way up to their ascending top set.

Pros of Ascending Volume

Self-limits total load used in a session.

When enacted as a secondary, which usually will be used as a lighter session, or at least lighter than the primary, ascending volume will increase relative exertion while keeping absolute load lighter.

The analogy I like to use for my lifters is: if you had to take heavy single, will you be stronger/have the weight feel better if you took a single as your last warmup, or a set of 5 at that same weight? I would hope intuitively we know the first option would be the case. Same concept here.

For athlete’s that are very strong in an absolute manner, think your heavy hitters who are squatting and deadlifting in the 700lb range, this can aid in keeping the athlete healthy while also providing mental stimulation from the challenge they provide.

Provides mental stimulation for otherwise easy sessions.

Now, this might be rather remedial, but I actually find a merit in having something to look forward to in the gym and days you are not going as heavy.

Early on in my career, it was very tough to go into the gym knowing I am capable of 150lbs more on a given lift, for the same rep range, but simply not doing that for a host of reasons that range from: it is early in the cycle, it is a secondary or tertiary session, or, I am simply not feeling the greatest to do so.

I find that for lifter’s who are very, “things need to be heavy for me to feel like I worked out”, you can add ascending volume in to meet halfway. Especially if it is a novel stimulus, the challenge of doing your best set of 5, with 2 hard sets of 5 before it, is unique in it’s own right and can provide other avenues of challenge that are not absolute weight.

I find when we lift an ascending scheme at the end of the cycle, athlete’s approach their top set with much more confidence. If they knew last week they got within 10lbs of their best rep set with 3-4 ascending sets before it, it is a forgone conclusion that a PR is their simply working up to a top end set.

Another seldom talked about concept is how mentally “on” you have to be for all ascending sets. When using a top set and backdown, I do not care who you are, it is almost never going to be the same mental stimulation for your top end set then your backoffs and that is when things tend to get sloppy.

Time-efficient way to accrue volume.

Simply put, I find ascending sets for most, do not take as much time to complete.

For reference, if you squat 600lbs and you are to take a set of 5 @ 7.5-8 that day, it might take you a bit to work up to 520-550lbs for 5, then let’s say you have 3 sets of 7 backoffs, you will probably need to take at least 5 minutes to recompose yourself and strip the bar, and then do your 7s that will require rest in between. Before you know it, an hour has passed by and you are still squatting.

This may speak to a greater issue, but I find for my parents who are pressed for time, my college lifters who have to lift between classes, it is more time efficient to use ascending loading schemes. Plus, it is not like you are starting with your first working set, you have to work up to the weight ranges as normal before you do that, so you are accumulating more than likely the same amount of volume, albeit at lower intensities.

Easier to decide loading for variations, odd rep ranges.

Early on in my career, it was tough to describe to people, what weight you should use for high bar paused squats for sets of 6, when they are a low bar squatter.

Not many people know their 7rm, they might know their best set of 10, best of 5, 3, 2, 1. But when we want to use a set of 7, or a set of 9, sometimes it is hard to gauge where we should start and where it is appropriate to end. Ascending loading allows you to feel out the progression in real time and allows you to perceive the loading within context of the RPE assigned. This falls a bit short if you are using hard percentages however.

In the example I provided, I had no clue what I could squat on the SSB, seeing as the last time I ran it was 2018 and it was sub 300lbs for a set of 6. Ascending loading allowed me to not only feel the bar out but also decide what was appropriate for weight jumps in a given session and each week. If I used a top set with backoffs from the jump, I would have most likely gone exponentially too heavy to start or spent the first 3 weeks going too light as I was still learning how to squat on the bar as it is distinctly different than a straight bar.

Be more accurate with RPE.

Now this one is the biggest reach, but I have seen that sometimes people take a final single as a last warmup and claim it felt awesome (which it probably did) only to fail rep 2 of a 5 rep set.

This is because for a lot of people singles and rep work does not scale the same. Nuance to this one for sure, but especially for newer lifters learning RPE, taking the same amount of reps before hand, allows you to make a more informed choice of what weight to use for a given set.

Application to accessory work.

Ascending volume works really well for accessory work. 3 sets of 10 at a straight weight has it’s merit, but if we are using it as a strength driver, a la, leg press, DB bench, dips, etc… We might have the same issue keeping force output up over the course of a 3 set span.

Cons of Ascending Volume

More fatigue inducing.

Yes, the same pro can also be a con. In phases where we really need accurate feedback on where our top end is at, it does not make much sense to artificially limit total weight used.

For lifters who are very forceful or very strong, an ascending set can zap their top end dramatically and let’s say we want to test, we are not getting the most accurate results based upon this principle.

Might not scale for each lift.

You might find some lifts tend to be better with ascending loading than others. My own lifters have reported it being easier to gauge on squat, deadlift and harder for bench press.

If you are a very fast-twitch, explosive lifter, you might find the dilemma of you feeling good and then dying out unexpectedly with ascending loading. An interesting phenomenon I see this is with close grip bench press for people who have not done it in a while, what feels light for a set of 10, flies for reps 1-7 then they hit a muscle failure wall at reps 8, 9, and 10.

First 1-2 sets might not be stimulating enough.

Yes, even I agree, this could be the case.

Some lifters try to cheat the system and take the weight jumps that conserve the most energy for their top end set, meaning, yes, the first set might be at a percentage that is on paper, too light to be beneficial for adaptation.

Ex. You REALLY want to hit 315lbs for 8, but know it won’t happen if you take, 295lbs, 275lbs before it so you take: 225lbs, 265lbs, 315lbs. Yay, you got your goal, but it is effectively the same as if we did a top set. This is more of a lifter education thing.

First 1-2 sets might be TOO stimulating.

Oddly enough, I have the opposite problem occurring more often in that people take the first 2 sets way too heavy, essentially over-shooting those sets, culminating in small jump in weight for the top end set.

Ex. You bench press 315lbs, and have 1x5 @5, 1x5 @ 6, 1x5 @7, but you took that first set @ 255lbs and were off by 1 RPE high, then you go up 10lbs and overshoot again, then finally you are forced to only go up 5lbs and either fail or barely grind out the 5th rep.

These 2 concepts are more rooted in lifter education and sometimes, to be real, need to be experienced first hand to know for future workouts. As long as the lifter is safely performing lifts and not decapitating themselves, it is actually a useful tool to know where the limit is early on. It’s counterproductive for equally as many reason, but there is merit to having that experience in your back pocket.

Top sets w/ Back offs

A somewhat typical top set scheme with backoffs. One of the limitations this method has is “sand-bagged” back off rep work that is either too light for stimulus, or not treated with intent necessary to develop good habits for successive sessions. Although this athlete has a percentage of their top set for backoffs, this is not the only way to program in backoff volume. Though multi-factorial, this athlete squatted a 22lb all time PR with this method.

Top sets with backoff work are the most common method powerlifters use when it comes to loading schemes. If we think about it as a whole, conceptually speaking, it makes the most sense in virtually every application. You come in, you work up to a given weight while you’re as fresh as you can be, and then you do a lighter weight for a given amount of reps in order to accrue volume/maintain working set count per week.

Some common ways to do this include:

Top set at given percentage, backoff work at a given percentage. Ex. 1x5 @ 75%, 3x5 @ 70%.

Top set at a given RPE, backoff work at a given percentage of 1rm. Ex. 1x5 @ 7-7.5, 3x5 @ 70%.

Top set at a given RPE, backoff work at a percentage of top set. Ex. 1x5 @ 7-7.5, 3x5 @ 88% of top set load.

Top set at given RPE, backoff work at given RPE. Ex. 1x5 @ 7-7.5, 3x5 @6-7

And there are other ways to implement this as well.

Pros of Top Sets + Backoff Volume

Taking advantage of highest energy during a given session.

Naturally, it goes without saying that we will have the most energy at the beginning of a session. So it makes sense to try to attempt our heaviest weights with the most energy and theoretically least fatigue. Nuance across the board, but being able to “take what is there on the day”, is easier without having pre-fatigue from something such as an ascending set.

As we laid out in ascending sets, it is easier to take a weight without having multiple higher rep sets on the way up to it.

In periods of testing, gives the athlete and coach accurate feedback.

Simply put, in a meet, you are after performance and your warmups are to prime you for each attempt. In the gym, this simulates the same thing and allows the lifter to feel out things such as: how big of a jump can they make, how many warmups do they truly need, and the the obvious, how do they move/feel when fresh.

Variable programming options.

As laid out in the example in the explanation, there are so many ways to implement a top set with backoff scheme that suit the athlete.

Want to give an athlete a heavy exposure but not bog them down with backoff intensity as they are very strong absolutely? You can use a top set with open ended RPE, then a larger % drop off for backoff work. Ex. 1x3 @ 8, 75% of top set load for 3x3.

Want to have the heavy exposure serve as a primer but feature heavier backoff sets to acclimate and be more efficient at higher % of 1rm? Load cap the top set conservatively and feature a less steep % drop off for backoff work. Ex. For a 500lb deadlifter, 1x5 @ 8, CAP @ 455lbs… 88% of top set load for 3x5.

Have an athlete that is very adept at pacing a training cycle, choosing adaptation-inducing backoffs? Make it totally RPE based. Ex. 1x1 @ 7, 3x5 @ 6-7

Better application to expression of strength.

If you want to get all the benefits of straight sets but not lose out on hitting heavier weights for technical reinforcement and skill practice, a top set and back off scheme works very well.

Allows for more accurate auto-regulation.

This is a reach here, however I have heard the case that top sets allow someone to auto-regulate easier and not force the issue with something like straight sets or ascending volume, however this is a weak argument that I can only 1/2 heartedly stand by.

Cons of Top Sets + Backoff Volume

The athlete might start to view training as testing.

When we are constantly working up to heavy top sets, we are really testing what is there on a given day. As we may or may not know, strength and skill can be fairly volatile over the course of a training cycle.

If this is all we do, an athlete could start to develop an identity around certain weights, certain ranges, certain RPEs, that does not allow for progression and causes frustration when it does not go their way in a given session.

Training at points can become demotivating.

Look, we all go through spells where we are not at peak strength. If an athlete is coming off injury, or training lay off, and multiple times a week they are reminded that X weight that used to be easy is now hard or not even a possibility, it comes tough to want to even do that workout.

Sure, it is one thing to be disciplined, but it is another thing to have your desire to train wane because you cannot work up to what you once did or you are programmed much lighter top sets on a secondary day that don’t provide you the same psyche and ego boost you are used to.

Inappropriate at times with secondary, tertiary, or accessory driven work.

It just straight isn’t necessary to hit a top set every time you walk into the gym. If you have a recovery based or priming day, yes, you may use a top set, but 80-90% of the time, you are using the to grease the groove to bridge you into a heavier session.

For single joint accessory work, it doesn’t really necessitate high force output, hence no need to “backoff”.

It can create a situation where an athlete feels they need a top set to feel strong and paralyze other aspects of training because of it. Introduction to different training stimulus is generally a good thing early on to establish the athlete’s understanding of why and when you use such methods.

Prone to non-productive volume training.

I think we all have had a session where you have a 1x1 @ 8 then 3 sets of 6 backdowns @ 7-7.5, where in reality those sets were like 4-5 as you did not have the mental wherewithal to try much harder than that.

In phases where we need productive rep work to drive adaptation, this becomes a big issue. You could make a case that the top set is actually a nuisance at this point.

For some athletes, I have removed the secondary top set in a week, for this reason.

Straight Sets

One of the most popular beginner strength programs is the Texas Method. It enacts the same weight across a set amount of working sets, with no variation up or down. If you are a barebones beginner, sometimes this is more appropriate than anything, however, you quickly realize it’s limitations as you get higher and higher towards 1rm with a given rep range.

Straight sets are probably the easiest to understand for most novices and beginners. You are doing the same amount of reps each set, at the same RPE or same % of 1rm. As shown in the example of the Texas Method, you are to do 5 sets of 5 reps @ 90% of your 5rm. So, quick math here, if your 5rm squat is 405lbs, 90% of that is: 365lbs. You will perform 5 sets of 5 reps at 365lbs.

In almost all beginner templates, you will see something similar to this. Why? Because it is very easy as a beginner to progressively overload and in turn, get stronger, with minimal thought and effort outside of lifting the actual weight.

Pros of Straight Sets

Better application to beginners.

If someone has barely lifted before, or their goal is to not lift for top end strength but rather “general” strength for a sport, it is so easy to say, 3 sets of 3 @ moderate to heavy.

Saying to do a set of 5 @ 7, then 88% of that for 2 sets of 8, is operating the assumption the lifter has a true understanding of RPE, a gauge of where their best set of 5 is, then they have the capacity to do 8s at that little of a load drop.

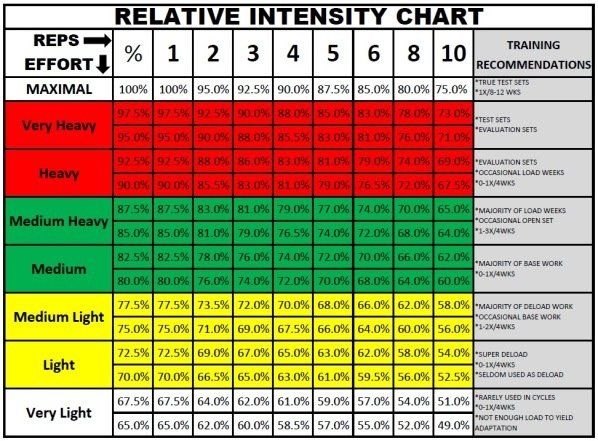

Better application towards relative intensity.

If you are familiar with a relative intensity chart, essentially, certain rep ranges correlate to certain effort levels within a percentile of 1rm.

If that made no sense, essentially, 74% for 6 should correlate to a medium-heavy working range, so if you gave an athlete, say, 72.5% for 3 sets of 6, they should be able to complete this without the workout getting excessively hard.

Although not correlative 1-1 for everyone, relative intensity stays fairly constant for the average lifter.

Not as much emphasis on a top end set.

With ascending or top sets, there is a bit of a “make it count for this one” approach to the final set of the ascending scheme or the top end set for the top set scheme, which may rob a lifter of what was a good session up until that point, but for whatever reason fell short for the highest set.

With a straight set, you have more opportunities to fix mistakes at similar intensities.

Generally speaking, a top set is usually heavy enough to warrant a re-take being counter productive and double time for an ascending set, for the straight set, this is not really the case.

Depending upon the scheme you use, it might be easier to be variable with loading.

If you use a true RPE approach, you may find lifters scale RPE a bit better with straight sets, meaning, they will autoregulate up or down based upon how each set goes. So in a way, this could become an ascending or top set scheme very quickly, though not the intention.

Cons of Straight Sets

May not be able to sustain same effort across sets.

Early on in my career, I was a massive fan of straight sets and followed a typical beginner periodization of adding a set amount each week.

5 sets of 5 at 225lbs was easy enough, the next time so was 235lbs, but as I got closer to 275lbs, I would be near failing the 5th rep by set 4 and only getting 3 reps by set 5.

You could argue, at this time, I would be better off adding weight to 1 set, taking weight off the other sets and getting the same amount of working reps while not drastically fatiguing myself for the next session.

You will learn quickly that sustaining a high intensity across multiple sets requires excessive rest time and many times, doesn’t actually carry over to top end strength output due to specificity. Ex. 5 heavy sets of 5 @ 87% does not mean 1x1 @ 98% will be any easier, for a healthy portion of lifters.

May not apply well to lifters who are advanced or of a high absolute strength level.

Simply put, I am not aware of many lifters, if any, who do 5 sets of 5 @ 80% on a lift over 600lbs, certainly not over 700lbs.

You see, going hand in hand with con #1, regardless of strength level, absolute weight on the bar matters. 5 sets of 5 at 225lbs is not the same hit to the system as 5 sets of 5 @ 650lbs. Don’t believe me? What should in theory be a medium easy workout on the first example (5,625lbs of volume) turns into an all out soul-snatcher in the second (16,250lbs of volume).

Generally speaking, our advanced or high absolute strength lifters will have enough force output for a single bout and will need much lighter weights to accumulate their working reps and training volume.

May not apply well to powerlifting performance as a whole.

If you are doing 2 sets of 3 leading into the meet, and assuming that what you hit for 2 sets of 3 should be your opener and then you can send it from there, you will be mistaken come meet time and if not, you more than likely got lucky.

I think most modern coaches would agree, although singles do not need to be maximal, they do need to be performed at some point in order to gain the skill acquisition necessary to perform in a meet as well as give regular data points to the coach. I do not care who you are, there is a distinct mentality brought to a somewhat heavy single that is not present in even the heaviest of rep sets.

Maybe it was common practice to go to a meet after 2 strong doubles in decades past, but that is not the game anymore.

If using hard percentage, can leave lifters feeling overly optimistic or overly defeated based on a given workout.

As stated before, 5 sets of 5 @ 87.5% going well, does not indicate 1x1 @ 102% will fly.

Conversely, on a day where you felt terrible and were programmed 3 sets of 8 @ 72% and they were all maximal and required you to psyche up only to fail rep 6 on your final set, does not indicate you got weaker and are regressing, you just had a poor day.

I Know The Pros and Cons, But How Do I Implement Into My Own Training?

This athlete of mine enacts ascending sets and top sets within his programming for barbell lifts, his accessory work many times will be straight sets.

Another lifter of mine has top sets, ascending sets, and straight sets in his programming for barbell lifts.

Although I would love to give you an idea of where to start, I think the best practice with this is trial and error.

For my lifters, I try to stick to a scheme that on average works in our first block based upon lifters of a similar build and background, then we plug and play based of that.

Are we finding we cannot add weight efficiently on a secondary day? Maybe we back off ascending sets and use a top set, backdown scheme.

Are we seeing consistently that their ability to repeat effort dwindles? Maybe we move on from straight sets in favor of another scheme.

Is it becoming less motivating to work up to a heavy set and leave the gym without challenge? Maybe we throw in ascending volume.

Is a lifter borderline too strong for their own good and in turn, we have to start artificially limiting loads per session to keep accumulation of fatigue from effecting other areas? Maybe we add ascending volume in.

The possibilities are endless really. But you don’t know until you try.

The progression of my career was all straight sets, to all top sets, to top sets with straight sets, to top sets with ascending sets and we still are there today. This was over the span of 5 years though, I did not learn this within a block or 2.

As with anything, be patient and look at the data that is being provided to you.

If something consistently is not working, it is time to switch it up. However, if something is working, then you better have aggressive reasoning to want to switch up, take it from someone who has had full year spells without PRing a lift!

Hope you found this helpful!

To Utopia,

Erik